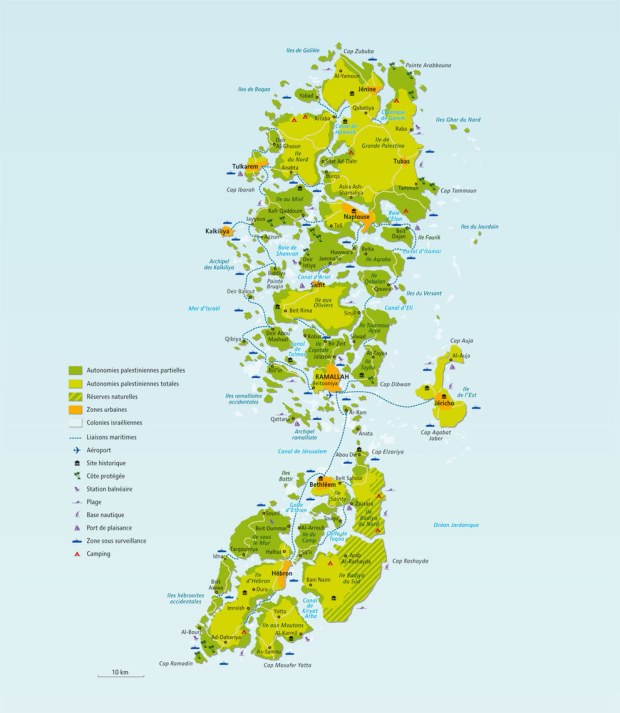

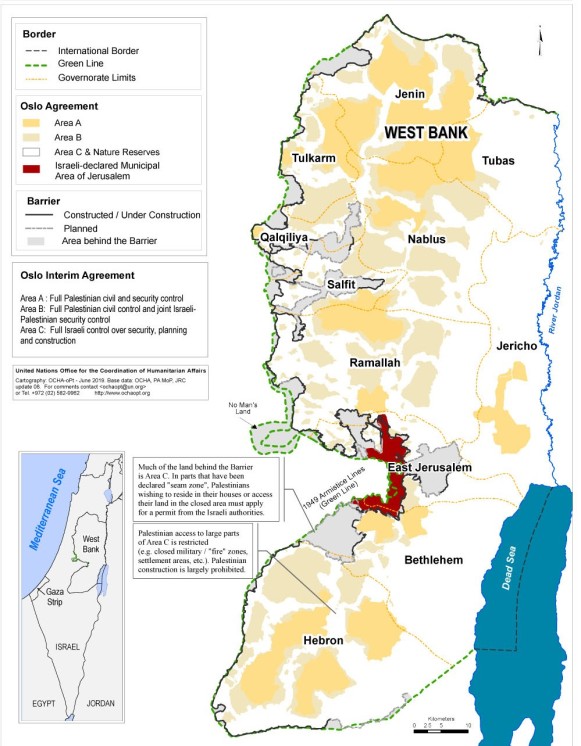

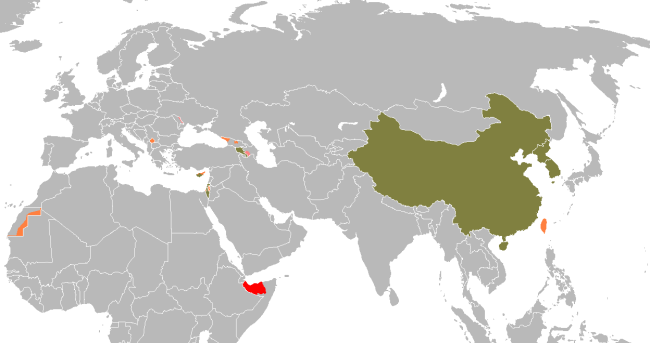

Palestine is a place that doesn’t exist in a legal-administrative way: it is only partially internationally recognized (but still not a member of the UN) and although – according to the Oslo Accords – possesses some sovereignty, in practice this is severely limited. However, Palestine is recognized by more than half of UN member countries, and is part of some UN bodies, which allows it to voice its opinions and grievances on the international scene. Compared to the de facto states in Eurasia, it receives much more international media attention and has a strong international presence, with many NGOs engaged in monitoring and documenting violence and human rights violations. Israel knows that large-scale violence and land seizures will not go unnoticed and will harm its reputation, but also cause economic damage. In order to pass under the radar and escape the watchful eye of media and NGOs, it resorts to what Foucault has termed the microphysics of power.

In my previous post I have argued that the “separation barrier” is the externalisation of Bentham’s Panopticon. I focused on the slow violence of architecture and urban planning. This time I would like to explore the shift from Panoptikon as a specific form of mechanical surveillance to panopticism as a form of social control behind the microphysics of power. In other words, I am interested in how the static, dehumanized elements of occupation (walls, fences, checkpoints) relate to – and are supported by – the dynamic elements of occupation (human activity).

OCCUPATION: SMALL STEPS AND GIANT LEAPS

One of the perceived differences between de facto states in Eurasia and Palestine, is that the former are widely (if incorrectly) seen as frozen conflicts, while the latter is very much still a hot conflict. One of the consequences is that there is no status-quo: the de facto control over territory changes daily with new “facts on the ground” being established through progressive occupation. Foucaultian approach to political violence seems taylor-made for the analysis of the microcosmos of occupation in Palestine. Foucault’s structural analysis takes into account both external (territory) as well as internal aspects (human thinking and behaviour), the geopolitical as well as biopolitical elements of political violence. This post is an attempt to frame my visit to the village of Bil’in and the city of Hebron in terms of Foucault’s concept of the microphysics of violence.

Occupation proceeds through small steps and occasional giant leaps. While the small steps consist of seemingly spontaneous local grass-root activity, the giant leaps depend on nation-wide administrative measures that legalize land grabs through court decisions. Both tactics fulfil the purpose of the larger strategy of pushing Palestinians out of their historical lands and are in contravention of Oslo Peace Accords.

The strategy of small steps itself appears to be twofold. The first part is carried out by Israeli settlers expanding their settlements through legal and illegal measures (often acting with impunity in full view of the army), such as burning olive trees, putting up fences, placing trailers on Palestinian land, and thus establishing “facts on the ground”. The second part consists of making life difficult for the Palestinians so that they would leave the land. This is done by constant harassment by the army and the settlers. The army operates through structural violence of the apartheid-like system of restrictions on movement; the complex system of checkpoints and permits, which create significant obstacles for locals to access their land, maintain contact between each other, and access services, such as healthcare. The settlers complement the “cold” violence of the army with “hot” violence ranging from harassment and verbal abuse to extreme acts of violence, such as the recent arson attack in Nablus, where a baby and his father were burned to death. In order to look at how violence operates on the micro level, I draw on my observations from Bil’in and Hebron.

BIL’IN AND THE HORIZONTAL VIOLENCE

The name of Bil’in – a village located 12 kilometres from Ramallah – resonates with very few people internationally. Yet, many have seen the Oscar-nominated Five Broken Cameras, which was shot entirely in the village and surrounding areas. A Palestinian-Israeli coproduction, the film depicts the struggle of villagers – mostly farmers – to hold on to their land, which has been seized by the Israeli military for the construction of new settlements and the West Bank security barrier. The villagers have been organizing protests every Friday after prayer for the past few years. Israeli army has mostly responded with arrests and fired tear gas at the protesters. As the tear gas bombs were not shot at an angle, but directly into the crowd, people have been killed and injured, with empty tear gas canisters still littering the edges of the village – a harrowing reminder of the ongoing violence.

Talking to the people in the village, one gets a more intimate impression of how life on West Bank borderlines unfolds. Everyone you talk to has several friends or relatives who were arrested, injured or killed. In Bil’in geopolitics and bipolitics become intertwined as the conflict for territory unfolds through the use of human bodies as the only source of resistance. Stripped of legal rights and territory, the villager becomes a Homo Sacer – left only with his or her bare life, an outcast liable to persecution and violence with impunity. In Palestine everything is political, down to human life in its most bare, basic form. To exist is to resist.

From any point in Bil’in, one can see the Israeli settlement Modi’in Ilit and its satellites Ne’ot Hapsiga and Green Park. The villagers of Bil’in are not in conflict only with the army, which only intervenes in protests and enforces land grabs. They are in an ongoing conflict with the settlers, who have on several occasions initiated violence against the Palestinians; stealing their land, destroying their property, and beating up the villagers.

HEBRON AND THE VERTICAL VIOLENCE

Hebron has perhaps the tensest atmosphere of all the conflict areas I’ve visited in unrecognized states. One reads of periodic incidents in the media, but on the ground the tensions that escalate into violence occur on daily basis. Moving around the West Bank, one becomes used to horizontal divisions of territory with walls, fences, checkpoints and bypass roads separating Israeli and Palestinian areas. In Hebron, the division is as much vertical as it is horizontal. Israeli settlements surround Hebron, but in the old town they are also placed on top of Palestinian houses with Palestinians living on the ground floor and Israeli settlers occupying the first – and in some cases – the second floor. The conflict here also assumes a vertical dimension with settlers throwing rocks, trash, glass bottles, eggs, and spilling urine and bleach down on the Palestinians in what is the main market street of the town. In the complex legal-administrative vacuum the Palestinian police cannot prevent settlers from these hostile acts since it has no jurisdiction over them, and the Israeli army, which possesses this jurisdiction, has no intention to prevent violence, restricting itself to observing the whole situation from their guard posts on rooftops. The three layers on which the conflict unfolds in Hebron symbolise perfectly the wider situation in Palestine: Palestinians are on the bottom, under the attack of Israeli settlers above, while the army on top does nothing at best or takes the side of the settlers at worst.

Items thrown by the Israeli settlers on the people in the market street and the makeshift mesh put up by the Palestinians to defend themselves. Hebron

According to Foucault, surveillance and discipline eventually become internalised so that the bulk of repression is carried out by the repressed themselves. In order to defend themselves, the local residents put up a makeshift metal mesh – a vertical analogue of the horizontal wall separating them from Israel. The Israelis have achieved the ultimate goal: the Palestinians are forced into building their own walls, their own prison.

Coming out of a Palestinian house, where we were hosted for lunch by a local family, we encountered a group of French Jews visiting a nearby Israeli settlement. They seemed agitated and we learned from our Palestinian guide that a few moments ago, they were engaged in a conflict with local people following which one Palestinian was arrested. Upon crossing the military checkpoint and entering the settlement, they approached us and started questioning us about the purpose of our visit, behaving in an abusive way. Despite our assurances that we are tourists who want to visit both the Palestinian and Israeli parts of Hebron, they were convinced that we are supporters of the BDS movement and were openly hostile towards us. It took the soldiers at the checkpoint to intervene and send them away. Had we been Palestinians, we would have been arrested and taken away “for our own security”.